Short-term Canadian outlook is lacklustre, but nation-building plan bodes well for long term prosperity

The U.S. trade war is, not surprisingly, hammering Canada’s economy. Last quarter’s sharp contraction of output, due to plummeting exports, means Canada is now on track to see its GDP grow by about 1.1% in 2025, which is well below the economy’s potential. And because of persistent structural problems i.e., beyond cyclical factors such as the ongoing trade war, 2026 is not looking great either. In this Economic and Financial Market Update, we explain what that means for inflation, interest rates, and the Canadian dollar going forward.

On track for a third consecutive year of sub-2% growth

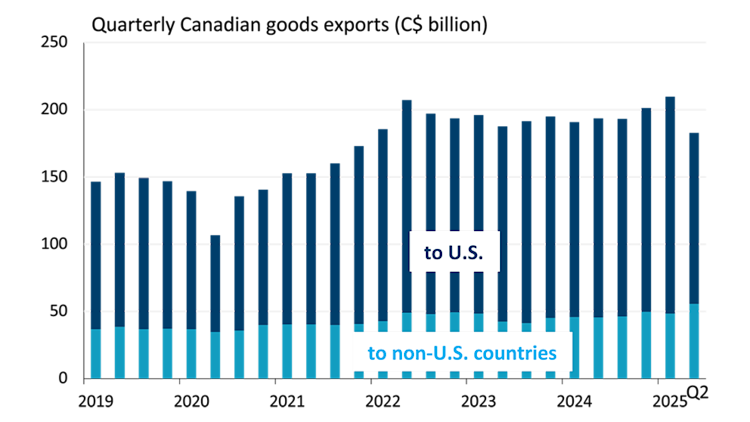

Canada just witnessed the biggest economic contraction since the COVID-19 recession, courtesy of the U.S. trade war. Exports dropped sharply as American tariffs were imposed on Canadian steel, aluminum, and CUSMA non-compliant goods, leading to real GDP sinking 1.6% annualized in the second quarter. Efforts to diversify trade away from America helped raise exports to non-U.S. economies, but not enough to compensate for the Q2 slump in U.S.-bound exports (Figure 1). Also disheartening was the fact that part of the GDP decline last quarter was due to sinking business investment, which further weakens the economy (more on that later).

Figure 1. Higher exports to non-U.S. countries did not make up for slump of U.S.-bound exports

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

Even the few positives of the Q2 GDP report had major caveats attached. For example, government current expenditures, which surged last quarter, are likely to give back some of those gains in the second half of the year. Ditto for consumption spending growth, which is set to soften drastically after the Q2 uptick given ongoing labour market softness and decline in the household savings rate to just 5%, the lowest in over a year. And finally, inventory accumulation, which significantly contributed to GDP last quarter, doesn’t bode well for production ahead.

So, odds are that any output rebound in the second half of the year will be modest, leaving Canada on track for GDP growth of around 1.1% in 2025. That would be the third year in a row of sub-2% growth, which highlights the fact that Canada’s economic problems run deeper than just cyclical factors like the ongoing trade war. The persistence of structural issues suggests to us that 2026 won’t be a great year either.

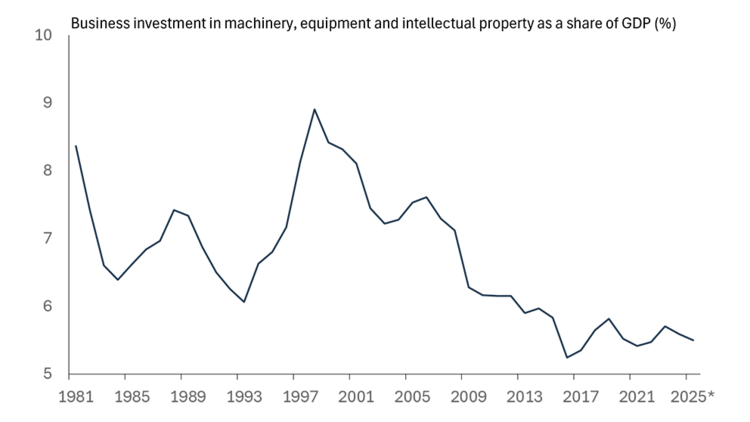

Weak business investment caps productivity

For instance, a low potential GDP i.e., the economy’s speed limit, due to stagnant productivity and a sharp slowdown in population growth, continues to restrain economic growth. The chronically weak productivity growth is largely a result of tepid private sector investment. Note that business investment in machinery, equipment and intellectual property has consistently fallen as a share of GDP to reach just 5.5% in the first half of 2025 (Figure 2). It’s no coincidence that labour productivity growth averaged a meagre 0.6% per year since 2002, about one third of the pace seen over the period 1981-2001.

Figure 2. Business investment continues to stagnate

*2025 estimate based on Q1 and Q2 data of that year

Source: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

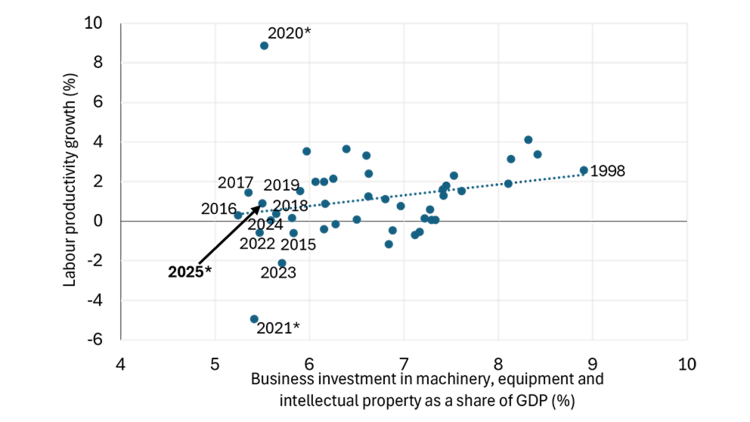

Raising business investment as a share of the economy should yield better productivity growth (Figure 3), boosting the economy’s potential in the process. This is, however, easier said than done. Multibillion-dollar tax incentives offered by the American government are difficult for any country to compete against in the race to attract foreign capital. A sinking Canadian dollar can also be a deterrent for foreign investors seeking stability, while also making imported machinery and equipment more expensive.

Figure 3. Positive relationship between productivity and investment share of GDP

*2025 is based on Q1 and Q2 data of that year. Also note that in 2020, hours worked fell sharply due to the COVID-19 recession, which artificially boosted productivity growth. The opposite happened in 2021 as the labour market recovered.

Source: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

If you build it they will come

That’s not to say Canada should just give up in the competition for foreign capital. The country can leverage its strength in other areas to attract capital e.g., a world-class education and highly trained professionals, the abundance of natural resources, free trade with more than 50 countries, a trade agreement (i.e., CUSMA) and proximity to the world’s largest economy.

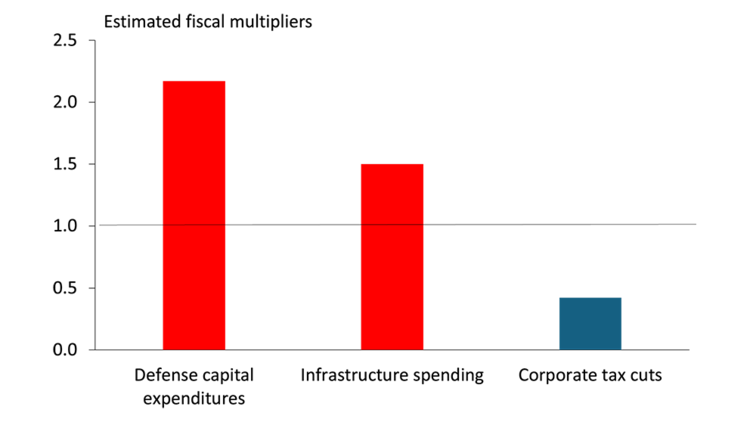

Modernizing Canada’s infrastructure can also entice foreign investors. That is why the federal government’s plans to boost expenditures on defense and infrastructure (via the Building Canada Act) are welcome news. Such outlays can lead to larger changes in real GDP, with one dollar spent generating more than one dollar of output i.e., a “fiscal multiplier” larger than one (Figure 4).

Such high multipliers are possible due to positive spillovers of those expenditures into the private sector, and they can be even higher if the spending occurs during periods of economic weakness. For example, defense capital spending such as research and development often leads to technological innovations that spur other investments and boosts productivity across the entire economy e.g., internet, GPS navigation. And spending on infrastructure such as roads, railways, ports and pipelines can open up new markets for exporters and, as a result, increase private sector investments in sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, mining, oil and gas.

The nation-building plan, however, may take some time to yield shovel-ready projects and stimulate economic activity. As such, the burden of rekindling Canadian growth over the short-term arguably falls on the Bank of Canada.

Figure 4. Infrastructure and defense spending can have large multipliers

Sources: Canadian Global Affairs Institute, Global Infrastructure Hub, PBO

Bank of Canada can provide near-term support

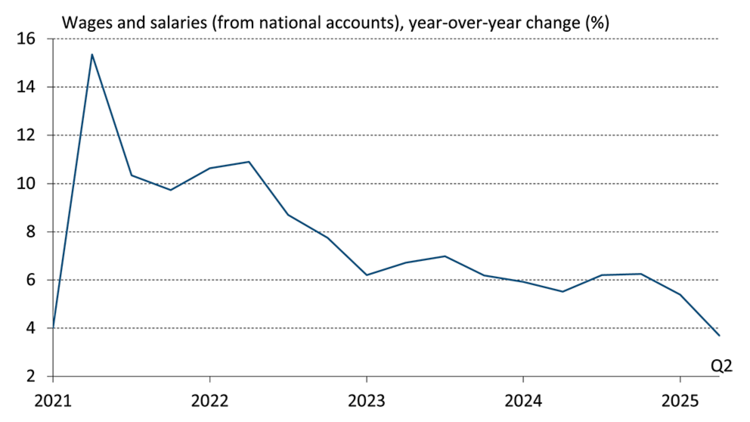

The central bank will be comforted not just by the recent moderation of inflation but also an increased likelihood that the latter remains under wraps. Indeed, the deteriorating labour market has led to wages and salaries growing just 3.7% year-over-year in Q2, the slowest pace since 2020 (Figure 5), reducing the need for businesses to pass on those costs to consumers via prices. That, coupled with the removal of retaliatory tariffs, and a widening economic slack or output gap (courtesy of below-potential GDP growth), suggests to us that core inflation will continue to soften into 2026. As such, the Bank of Canada, which lowered its policy rate to 2.50% in September, will likely offer additional stimulus over the coming months as it works to prevent the ongoing slowdown from turning into recession. So don’t be surprised if the overnight rate falls below the neutral rate’s estimated range of 2.25-3.25% before year-end.

Figure 5. Moderating wage growth gives BoC room to offer additional stimulus

Source: Statistics Canada

While short rates have room to fall further, barring a recession longer term rates are likely to remain elevated and sticky, driven by external factors, as we explained in detail in last quarter’s Economic and Financial Market Update. In other words, the yield curve could steepen over the next year. This means borrowers tapping into variable rate products will see lower debt servicing costs. But for those households renewing their fixed-rate mortgages, whose rates are often tied to the 5-year Canadian bond yield, there may not be much relief from here.

Mixed outlook for the Canadian dollar

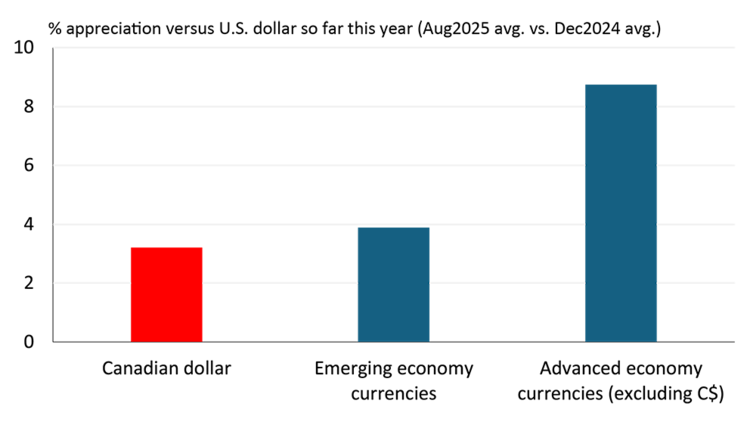

The outlook for the Canadian dollar is harder to decipher. The loonie has benefitted from generalized U.S. dollar weakness since the start of the year, but less so than other major currencies (Figure 6), highlighting some underlying issues with the Canadian currency. The Q2 export decline, which caused the current account deficit to jump to 3.4% of GDP, the worst since 2020, undoubtedly weighed on the currency. Net divestment from Canadian portfolio securities by foreign investors in the first half of the year, amid a dull economic outlook, did not help either.

We believe those mixed dynamics i.e., U.S. dollar weakness offset by weak domestic economic fundamentals, will persist over the near to medium term, leaving the loonie trading in the 72-74 U.S. cents range over the next year or so.

Figure 6. Canadian dollar has underperformed against currencies of countries other than U.S.

Sources: U.S. Federal Reserve, FCC Economics

Bottom line

Canada is set for another year of sub-2% GDP growth in 2025 but, worse, it also faces the prospect of being stuck in low-growth mode for years to come unless it can sustainably raise its economic potential. In that regard, the federal government’s nation-building plan, via capital expenditures on infrastructure and defense, is a step in the right direction because it can boost not just growth but also the economy’s potential if they spur additional private sector investment. But that plan will take time to be fully deployed, meaning any immediate relief to a weakening economy will have to come from the Bank of Canada.

With wage growth moderating and retaliatory tariffs being removed, the central bank will feel it now has better control of inflation, allowing it to lower its policy rate further. We would not be surprised if the overnight rate falls below the neutral rate’s estimated range of 2.25-3.25% before year-end. That will provide some relief to borrowers using flexible-rate products. But long-term bond yields are likely to remain elevated and sticky due to external factors, meaning that borrowers renewing fixed-rate products such as mortgages (whose rates are often tied to long term government bonds) may not get much of a reprieve.

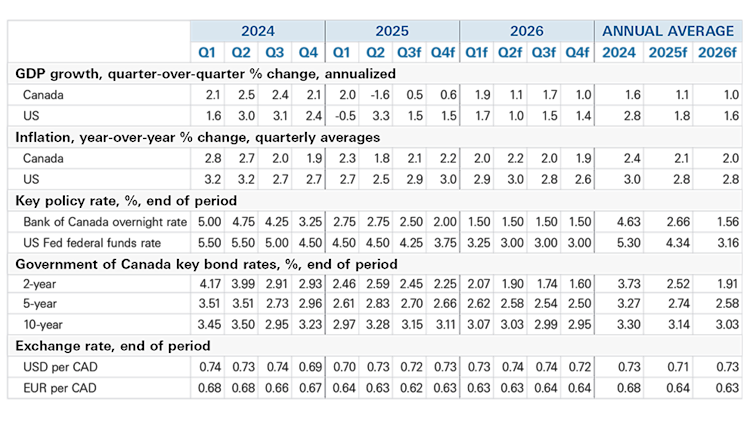

Summary of forecasts of key economic variables

Sources: Bloomberg, FCC Economics

Krishen Rangasamy

Manager, Economics, Principal Economist

Krishen Rangasamy is the Manager, Economics and Principal Economist at FCC. His insights and leadership help guide research on topics related to macroeconomics and agriculture, which FCC and external clients use to support strategy and monitor risk.

Prior to joining FCC in 2023, Krishen spent over fifteen years as a macroeconomic specialist on Bay Street, including at two major Canadian banks, where he advised trading desks and helped lead economic research and forecasting. He also regularly appeared on leading business TV channels and written media with his insightful commentaries on financial markets. Before going into investment banking, Krishen worked as an analyst in the energy industry in Western Canada. Krishen received his master of arts degree in economics from Simon Fraser University.