What’s driving Canadian interest rates?

Long term interest rates have been on the rise despite the Bank of Canada cutting its overnight rate twice so far this year, indicating that factors beyond the central bank’s policy rate are driving borrowing costs. In this report we highlight factors influencing Canadian long-term interest rates, which can be useful for the millions of households and businesses who will have to decide on borrowing products amid upcoming loan renewals. We also present updated economic forecasts that reflect the impact of America’s trade war on Canada.

Economic outlook darkens

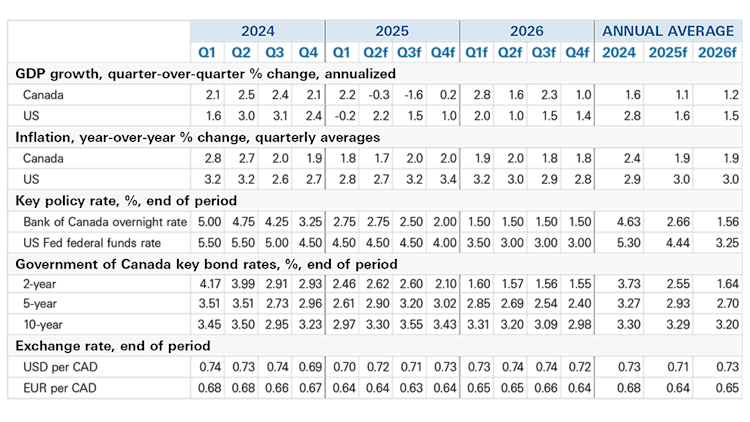

While Canada’s economy continued to expand in Q1, there are reasons to expect a sharp deceleration in subsequent quarters. There was a significant inventory buildup last quarter, which is not positive for production going forward. Also, uncertainties related to the U.S. trade war are likely to weigh on both trade and business investment going forward - the latter’s likely decline does not bode well for productivity growth and therefore the economy’s potential in the future.

Also concerning is the sustainability of growth in consumption spending (which accounts for roughly 60% of GDP). The labour market, which is already losing steam as evidenced by the surging jobless rate, is likely to deteriorate further in sync with weakening GDP growth. As such, one can expect household disposable incomes and therefore consumption, to be restrained going forward. Simply put, the economic outlook has darkened due to the U.S. trade war, and we have accordingly lowered our Canadian GDP growth forecast for 2025 to 1.1%.

If that new forecast pans out, that would be the worst annual growth rate since 2016, excluding the 2020 Covid recession. That also means the output gap (or excess supply) will open up, causing the currently resilient core inflation rate, to soften in the second half of 2025 and into 2026, and giving the Bank of Canada (BoC) more reasons to cut interest rates. We would not be surprised if the overnight rate, which was left unchanged at 2.75% in April and June, falls below the estimated range for the neutral rate of 2.25-3.25% by year-end.

This means the yield disadvantage (U.S. Fed policy rate minus BoC policy rate) could grow further this year. So, the Canadian dollar, which recently climbed to 73 U.S. cents, may find it difficult to sustain its ascent, especially given the weak economic fundamentals, both domestic and foreign - recall that weak global GDP growth, courtesy of America’s trade war and the resulting slowdown of world trade, is negative for commodities.

Canadian long rates dependent on what happens stateside

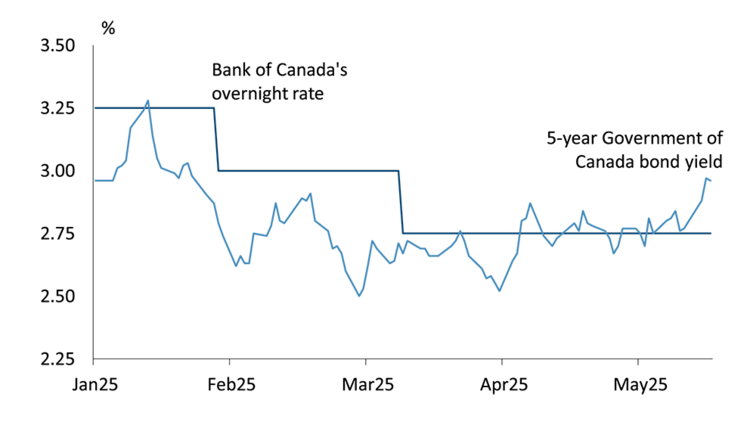

It’s unclear, if long-term interest rates will follow a similar trajectory as the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate. They certainly haven’t since April, with the overnight rate remaining steady while the 5-year and 10-year bond yields (and therefore fixed long-term rates set by commercial banks) have moved up, highlighting the central bank’s limited influence on long-term borrowing costs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Canadian bond yields on the rise despite Bank of Canada rate cuts

Source: Bank of Canada

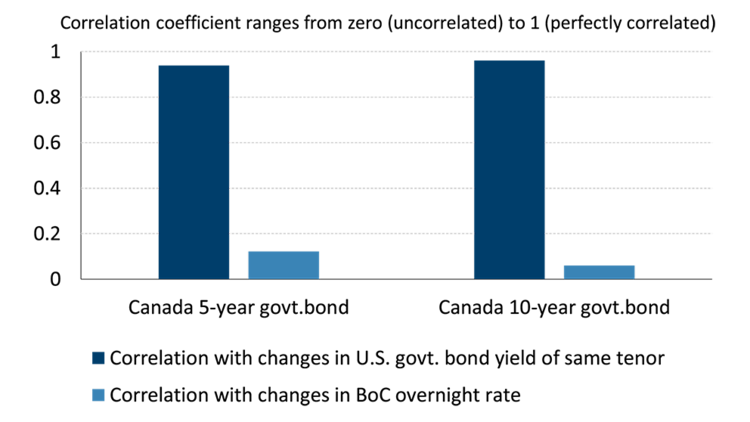

And that’s because Canadian bonds tend to be influenced more by U.S. bond market dynamics, as evidenced by the strong correlation between Canadian and U.S. bond yields (Figure 2). In other words, to forecast long Canadian rates, it helps to understand where U.S. government bonds are heading.

Figure 2. Canadian bonds are highly correlated to U.S. bonds

Sources: Bank of Canada, U.S. Federal Reserve, FCC Economics

Long-term U.S. interest rates are made up of two components

To make any sense of movements in the U.S. bond market, it’s important to understand that the long rate consists of two components, both of which are determined by the market.

U.S. government bond yield = Expectations about the future path of short-term Treasury bills + Term premium

The first component is expectations about the future path of short-term Treasury bills (T-Bills). Investors could choose to buy a 3-month T-Bill and reinvest the proceeds after three months in another 3-month T-Bill (a process called rollover) and keep doing that for several years. So, for investors to even consider buying a 10-year bond for example, they will demand at least the yield that they expect to get from the above-mentioned rollover over a period of ten years. Not surprisingly, the major driver of that first component is the Federal Reserve’s policy rate i.e., the fed funds rate, because the latter drives short rates such as T-Bills.

So, macroeconomic variables that guide the fed funds rate e.g., U.S. inflation, GDP, employment, the jobless rate, will influence that first component of long-term interest rates. U.S. GDP growth, which averaged a solid 2.8% over the last couple of years, is expected to not only decelerate drastically in 2025, but also to be well below the Congressional Budget Office’s 2.3% estimate for potential GDP growth. In normal times, sub-potential growth would translate to lower inflation. But because of tariffs (which raises the cost of imported goods into America), U.S. inflation could remain a problem over the near term even as economic slack opens up. That is why we expect the Federal Reserve to limit any stimulus to just 50 basis points of interest rate cuts in the second half of the year. This may put downward pressure along the yield curve, although not enough to guarantee longer-term rates also fall.

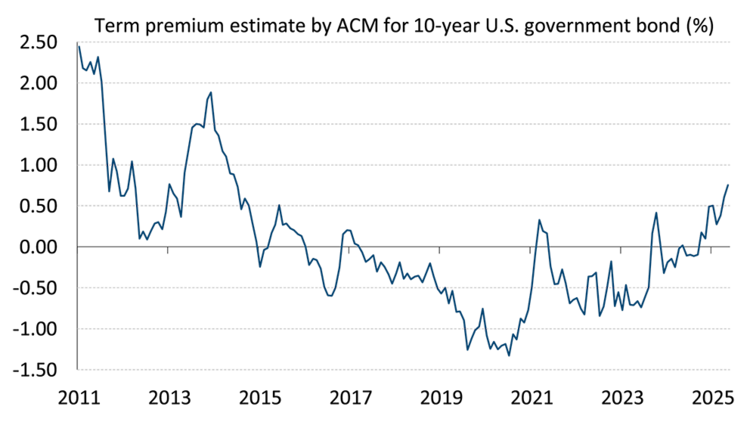

And that’s because of the second component of the long-term rate, the so-called “term premium”. The term premium is essentially the extra compensation demanded by investors for risks associated with lending to the government for longer periods – risks that can arise from inflation uncertainty, interest rate volatility, and macroeconomic shifts. The term premium is not directly observable, but it can be estimated using financial and macroeconomic models, the most commonly used being the one developed by U.S. Federal Reserve economists Adrian, Crump, and Moench (ACM).

Why the “term premium” is so important

Looking at data all the way back to 1970, we found that during U.S. recessions, the ACM term premium averaged about 75 basis points higher than during non-recession periods. That result should not be surprising because bond investors expect to be compensated for greater economic uncertainty and/or market volatility.

This year, amid changing trade and fiscal policy in the U.S., concerns have flared up about GDP and jobs, but also about America’s budget deficit, leading investors to demand compensation for extra risks of buying U.S. government debt. Indeed, the term premium, according to the ACM model, rose to 75 basis points in May, the highest since 2014 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Term premium is the highest since 2014

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve

Aside of America’s trade war, the debate around the U.S. debt ceiling will also be key in determining the term premium over the coming months. The debt ceiling will either be raised or suspended to allow the U.S. federal government to finance its obligations and avert a catastrophic default. But if the U.S. Congress is perceived by markets of not doing enough to address concerns about the massive budget deficit, further downgrades of U.S. government debt by rating agencies cannot be ruled out, a threat that may have investors demand an even higher term premium.

It's unclear how long it will take for the term premium to move back down towards its 15-year average of roughly zero. But when that happens, look for the disinflationary effects of widening economic slack (and corresponding expectations about a lower future path of short-term T-bills) to become more apparent in the bond market, lowering long-term U.S. yields in the process. Given the high correlation with U.S. bond yields, Canadian long yields (and therefore Canadian fixed mortgage rates) are likely to follow a similar path.

Bottom line

The recent uptick in Canadian long-term interest rates is primarily due to dynamics in the U.S. bond market. Enhanced uncertainties, particularly with regards to U.S. GDP growth, inflation and public finances may push up the term premium on U.S. government bonds even further, keeping long-term rates elevated for another few months on both sides of the border, to the chagrin of borrowers. As such, we would not be surprised if the Government of Canada 5-year bond yield, which is currently around 2.80%, moves above 3% over the next few months.

But the term premium on U.S. government bonds will eventually fall back as the above-mentioned dynamics fade. We expect that to happen by 2026, as evidenced by our forecast of declining long-term bond yields next year.

Summary of forecasts of key economic variables

Sources: Bloomberg, FCC Economics

Krishen Rangasamy

Manager, Economics, Principal Economist

Krishen Rangasamy is the Manager, Economics and Principal Economist at FCC. His insights and leadership help guide research on topics related to macroeconomics and agriculture, which FCC and external clients use to support strategy and monitor risk.

Prior to joining FCC in 2023, Krishen spent over fifteen years as a macroeconomic specialist on Bay Street, including at two major Canadian banks, where he advised trading desks and helped lead economic research and forecasting. He also regularly appeared on leading business TV channels and written media with his insightful commentaries on financial markets. Before going into investment banking, Krishen worked as an analyst in the energy industry in Western Canada. Krishen received his master of arts degree in economics from Simon Fraser University.