A wrap on the decade that was 2020 (January to June)

In our final blog posts of the year, we look at a year like no other. This first post covers January to June and describes the impacts to Canadian agriculture, food and agribusiness of the “before times” (January and February), the emergence of the pandemic (March), a global shutdown (April and May) and a faint promise of relief (June).

January

2020 was shaping up to be a good year. CUSMA was already ratified in the U.S., and Canada and the U.S. boasted the strongest western economies. The loonie was stable, having ended 2019 at US$0.77. Canadian exports were trending with the pace set in 2019 (or were better) for many ag commodities, including grains, oilseeds, pulses and meat. Even Canadian business confidence showed potential to continue rising from its 2019 low.

All of that was good news. There were, however, rumblings from China, especially concerning its trade with the U.S. A signed but suspiciously ambiguous trade agreement couldn’t signal an obvious end to their conflict. News of a devastating respiratory disease sent alarm bells off in public health quarters but few others. Both developments were troubling, given China’s important and growing role in price-setting across a broad spectrum of commodities. Still, only a few acknowledged the forces about to be unleashed upon the planet.

February

The first warning shots to Canada’s healthy status quo appeared on the horizon. China’s economy began to melt in direct response to the Novel Coronavirus and the lethal illness it produced. The world’s largest population was abruptly confined to their homes and the world’s largest manufacturer shut down operations. China is Canada’s second-largest agri-food export market, and such a meltdown worried observers. There had been undisputed benefits to Canadian livestock producers of China’s ongoing fight with the African Swine Flu. Would the boost to our exports continue? Moreover, the virus had spread beyond China’s borders. How would global markets react to the new threat?

Economic theory tells us the economic slowdown of a giant will likely disrupt the Canadian dollar, interest rates and trade. True to form, and although the largest declines in the loonie’s value were still to come, the CAD started to fall. Many assumed we would avert a global pandemic: a relatively rare inversion of the yield curve was one signal we might not.

March

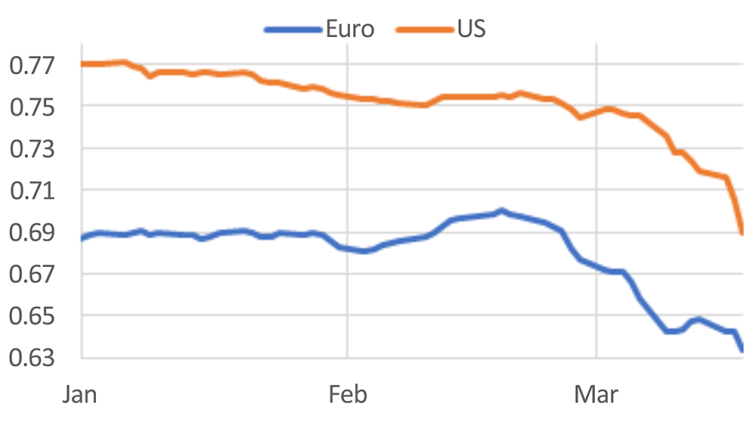

The “before times” crumbled in the face of COVID-19. By March, the virus had become a full-blown pandemic, a check on the global economy worth trillions. Across Canada, counter-COVID measures were hastily introduced. Our economy weakened. The loonie, forecasted in January to average US$.075 in 2020, tumbled to US$0.70 (Figure 1). The Bank of Canada lowered interest rates by 50 basis points.

Figure 1: Canadian dollar exchange rates with the US dollar and the Euro

Source: Statistics Canada.

Canadian exporters’ fears expanded beyond China’s consideration to include the U.S., by far Canada’s largest trade partner. Questions arose as to the U.S. market’s capacity to sustain demand and avoid recession, given that one-third of Canadian ag exports, and more than 70% of our food exports, go there. Would major Canada-U.S. supply chains be disrupted? In Canada, sectors employing seasonal workers were particularly threatened by the spectre of closed borders.

Almost lost in the news, Canada ratified CUSMA, a huge moment that would have dominated headlines in non-COVID times.

April

Corn growers’ prices dropped after USDA projections pointed to large 2020 acreage. Livestock producers saw big losses, as monthly animal protein production was slashed in the U.S. relative to April 2019 (24% for cattle; 30% for hogs) due to plant shutdowns caused by COVID-19. Hog futures dropped 25% in the last week of March, their biggest weekly loss ever. Canadian pork production saw a corresponding cut in that same timeframe.

The virus was also shifting demand for various dairy products. With restaurants, hotels and foodservice industries shuttered, demand for cream dropped while stronger fluid milk and butter sales highlighted the switch to home cooking. Such demand instability was global, reaching all sectors: markets’ lack of confidence in global economic strength briefly pushed oil futures negative this month.

The overall demand for food, however, remained inelastic throughout the early months of the pandemic. Food sales exploded everywhere, as global households stocked up and bought extras in the name of pandemic preparedness.

May

Because of increasing COVID-19 exposures in Canada’s packing plants, production continued to fall, prompting Canadian McDonald’s to source ground beef from the U.S. despite a commitment to buy Canadian. Given the potentially devastating losses facing the livestock sector, the Government of Canada launched an AgriRecovery initiative for cattle producers. A bright note: with roughly 50% of U.S. pork production also idled, wholesale pork cutout values skyrocketed.

The crisis further weakened the operating environment in 2020. Although no poultry processors had to shut down due to positive COVID-19 exposures, production quotas for May and June were cut by 12.5%. Demand for poultry had fallen so low it warranted the disposal of chicks and eggs.

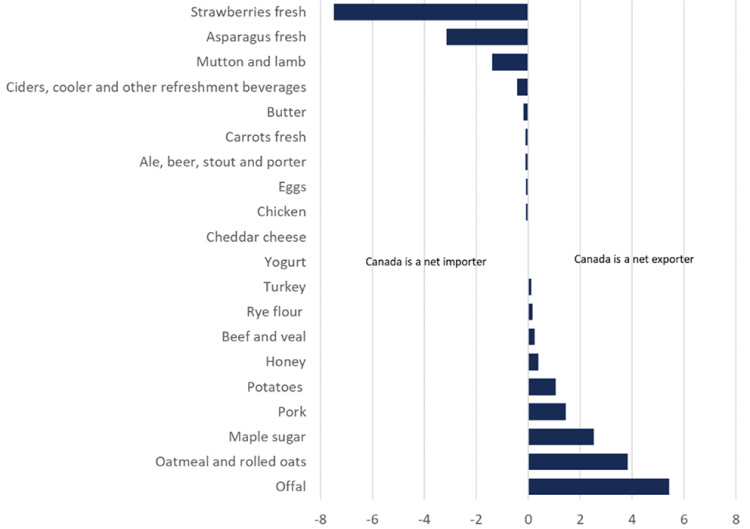

These gloomy indicators raised questions about the resilience of Canada’s agri-food supply chains. Canada consumes virtually all dairy and poultry produced here. Still, we depend almost exclusively on trade (Figure 2) to provide Canadians with certain foods (e.g., some fresh fruit and vegetables) as we rely on it to sell what we produce but don’t consume ourselves (e.g., meat offal).

Figure 2: Canada must trade for a strong ag economy

Sources: Statistics Canada and FCC computations.

Figure 2 shows trade dependence measured by an index. A value of -2 means that Canada imports twice as much of a product as we produce. Conversely, a value of +2 means that Canada exports twice as much of a product as we consume. Self-reliance implies a value near zero.

June

As global rates of infections, mortalities and hospitalizations slowed in summer’s warming temperatures, our first glimpse into Canadian agriculture’s financial health during the first quarter of 2020 showed mixed repercussions from COVID-19. Most hog producers felt few impacts on farm cash receipts relative to the first quarter of 2019, while grains and oilseeds receipts declined.

Figure 3: Canadian farm cash receipts by sector (billion dollars)

| Sector | Q1 2019 | Q1 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16.0 | (3.3%) | 16.9 | (5.5%) |

| Beef | 2.3 | (6.5%) | 2.2 | (-3.0%) |

| Dairy | 1.7 | (5.5%) | 1.8 | (5.9%) |

| Eggs | 0.3 | (9.7%) | 0.3 | (4.6%) |

| Hogs | 1.0 | (-8.4%) | 1.1 | (14.4%) |

| Poultry | 0.8 | (5.1%) | 0.8 | (8.4%) |

| Other livestock | 0.2 | (-10.1%) | 0.2 | (-5.2%) |

| Fruits | 0.1 | (9.9%) | 0.1 | (-1.5%) |

| Grains & Oilseeds | 5.7 | (-1.4%) | 5.6 | (-1.7%) |

| Greenhouse | 0.1 | (3.8%) | 0.1 | (-3.1%) |

| Potatoes | 0.3 | (7.1%) | 0.4 | (10.3%) |

| Vegetables | 0.3 | (4.9%) | 0.3 | (2.7%) |

| Other crops | 2.5 | (4.1%) | 2.9 | (16.1%) |

| Program payments | 0.7 | (60.2%) | 1.0 | (42.4%) |

Source: Statistics Canada Table 32-10-0046.

Note: Change from previous year in parentheses.

There was no escaping the damage, however. In June, FCC Ag Economics projected overall 2020 receipts to fall 3.4% year over year. Not surprisingly, our estimates of the sectors’ overall profitability also looked bleak. Although energy prices had fallen, the chance to capitalize on their decline was thin. The regions that were likely to be the most negatively impacted by COVID-19 were those with the largest shares of farm revenues from beef, dairy, hogs and potatoes.

What happened in the second half of 2020 would surprise many. Of course, the chaos and crises persisted worldwide as COVID-19 continued to ravage global populations, but for some working within Canadian ag, food and agribusiness sectors, hope for a good year was slowly materializing. Check back next week to discover the details.

Martha Roberts

Economics Editor

Martha joined the Economics team in 2013, focusing on research insights about risk and success factors for agricultural producers and agri-businesses. She has 25 years’ experience conducting and communicating quantitative and qualitative research results to industry experts. Martha holds a Master of Sociology degree from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario and a Master of Fine Arts degree in non-fiction writing from the University of King’s College.