Canada sees rising interest in controlled environment agriculture

As Canada continues to rely heavily on imported fruits and vegetables, especially during its long winters, different types of controlled environment agriculture (CEA) are gaining momentum to help overcome this problem. The goal is to support domestic production and reduce reliance on foreign supply. As trade dynamics evolve and consumers become more conscious of Canadian grown food, understanding the potential and limitations of CEA has never been timelier.

In this report, we build on previous work by exploring the strengths and opportunities CEA offers Canadian agriculture, while also highlighting weaknesses and threats it must overcome. While greenhouse-grown crops are the most recognized form of CEA, the category also includes other sectors like insect farming, aquaculture, lab-grown meat, and crops grown in vertical or containerized systems. We focus on fruits and vegetables grown in greenhouses, by far the largest and most established segment of CEA in Canada. However, many of the insights and trends discussed here are also relevant to other emerging CEA methods like vertical and container farming.

Strength: Yields outpace outdoor grown equivalents

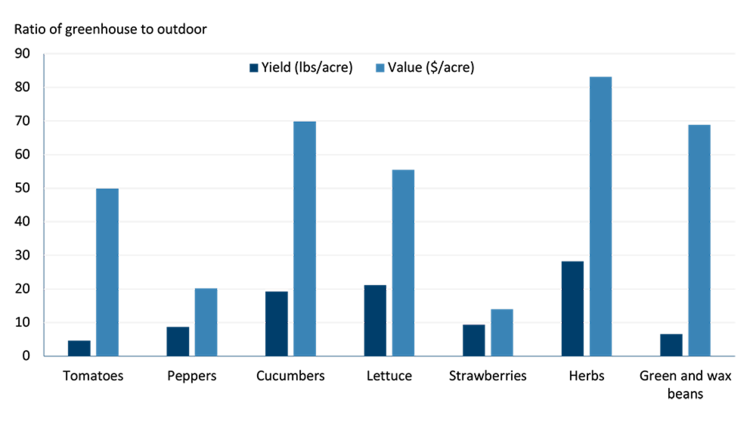

By extending the growing season and stacking crops vertically, greenhouse operations unlock higher yields than traditional outdoor farms growing the same fruits and vegetables. The advantage is striking, ranging from five times more pounds per acre for tomatoes to an impressive 30 times more for herbs (Figure 1). Part of this advantage is a result of the ability for greenhouses in Canada to operate for nine months of the year on average, with multiple harvests. Some vertical and container farms push this further with year-round production.

The space and time advantage in greenhouse production also translates into a higher farm gate value per acre. Again, herbs dominate this category followed by cucumbers (Figure 1). Even field-grown vegetables often get their start in these controlled environments, highlighting the strength greenhouses have in overcoming Canada’s typically short outdoor growing season.

Figure 1: Higher yields and farm gate value per acre for greenhouses compared to outdoor production

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

Weakness: Limited number of crops suitable for production indoors

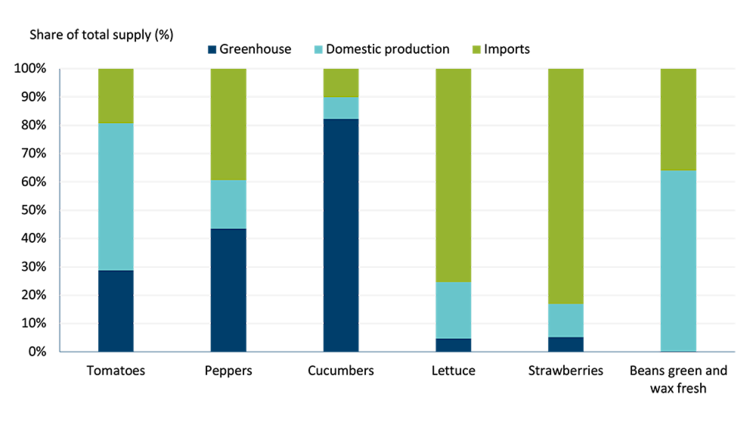

Despite their strength in yields, greenhouse production still meets only a fraction of national demand for many crops. Most fruits and vegetables on Canadian tables still come from outdoor farms or are imported. This is because many crops simply aren’t suited to controlled indoor environments and swapping them between indoor and outdoor systems isn’t as simple as it sounds.

In fact, only a few greenhouse-grown crops (e.g., tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers) make a large contribution to the national supply. Others, like strawberries, lettuce, and green beans, contribute only a small portion (Figure 2). Beyond these few, most fruits and vegetables that can be grown in Canada are still cultivated outdoors due to specific environmental needs that are difficult and costly to replicate indoors. For example, potatoes require deep, loose soil while cranberries need large amounts of water, conditions that challenge even the most advanced indoor systems.

Figure 2: Supply of select Canadian fruits and vegetables by origin

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

While innovation in CEA is advancing rapidly, expanding its reach to reduce Canada’s reliance on imports across a broader range of crops will require time, investment, and continued research. For now, the limited number of crops that thrive in greenhouses remains a key weakness of this otherwise promising production method.

Opportunity: Protection and resiliency in trade

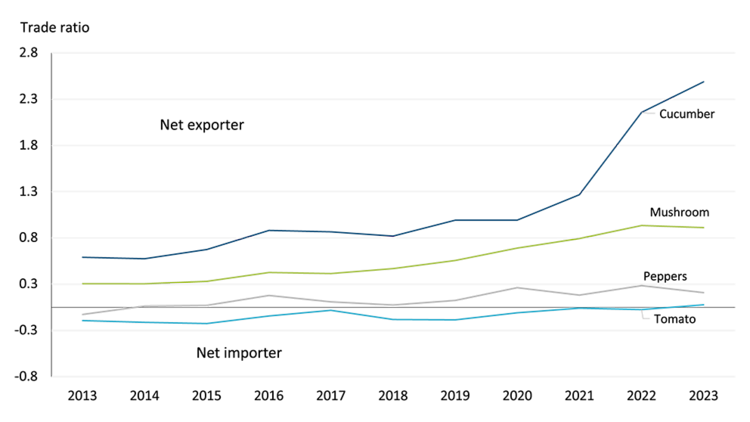

Exports of greenhouse-grown peppers, cucumbers, and tomatoes now meet or exceed imports. Canada is also self-sufficient in mushrooms, thanks to the ability to produce indoors year-round in a controlled environment. Between 2013 and 2023, Canada went from being a net importer of peppers and tomatoes to a net exporter, while strengthening the cucumber and mushroom trade balance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Canada becoming more self-sufficient in some fresh fruits and vegetables over time

Note: A value of zero means Canada is self-reliant, as domestic production equals consumption. A negative value means Canada is a net importer, while positive values mean a net exporting position.

Source: FCC Economics

The sector has also introduced new products and increased operations in more provinces outside of Ontario. For example, strawberry production in greenhouses was negligible before 2020 but reached 16.5 million pounds by 2024. In addition, there are 70 more operations and 19% more greenhouse area since 2013 outside of Canada’s largest concentration of greenhouses, Ontario.

There are opportunities for further expansion. For crops like lettuce, herbs, and strawberries, Canada remains a net importer despite increasing greenhouse production in recent years. Boosting output from these operations presents a clear opportunity to meet domestic demand, reduce reliance on foreign supply, and help stabilize prices for consumers.�

To realize this opportunity, Canada must invest in practices to boost productivity through labour and resource saving technologies, research and development for new crops, and explore ways to bring CEA to more regions.

Threat: Availability of inputs and markets pressure longevity

Setting up controlled environment farms requires substantial up front capital for land, buildings, climate control systems, LED lighting, and automation. These high startup costs sometimes mean preparing for longer payback periods and operating on a large enough scale to manage fixed costs while remaining price competitive against imported or outdoor grown produce.

In addition, CEA comes with steep operating costs and labour requirements related to the management of heat, moisture, and lighting based on the crop type and location of the facility. Operating expenses for greenhouses are rising, up 6.0% on average annually over the last decade. However, sales did increase slightly more at 6.4% over the same period, keeping margins a little above breakeven for the sector.

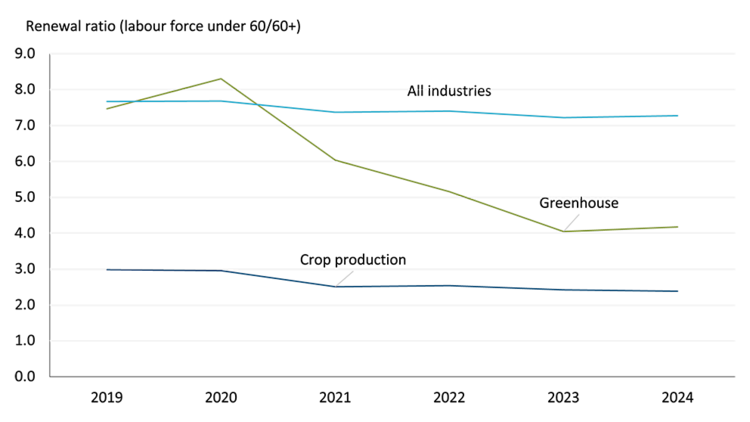

While rising costs are a challenge, the bigger threat is the availability of inputs. The under-60 workforce in greenhouse production has shrunk by an average of 8% annually over the past five years, and for every worker nearing retirement, there are only 4.2 younger replacements (Figure 4). At the same time, CEA businesses must compete with other high-tech sectors for limited municipal infrastructure like energy, water, and waste services, making expansion or new builds even more challenging or completely out of reach.

While technology may ease some of these pressures by helping to boost productivity, the sector’s ability to scale up production hinges on solving both the cost and capacity threat.

Figure 4: Ratio of younger workers to older workers in greenhouses falling quickly

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

Bottom Line

CEA offers a promising path to complement outdoor farming, by extending the growing season and delivering high yields. With innovation helping boost productivity and enabling the viability of a broader range of crops and growing regions, the sector is gaining momentum. However, CEA still represents a small share of Canada’s total fresh produce supply and remains limited in the variety of crops it can grow.

Investment and the adoption of technology will be crucial to overcoming high operational costs, address labour and infrastructure constraints, and allow the sector to reach its full potential. In the meantime, the supply of most fruits and vegetables in Canada will continue to come from imports and outdoor production.

Amanda Norris

Senior Economist

Amanda joined FCC in 2024 as an Economist. She has expertise in the food and beverage industries, but also does research on supply management and consumer trends. Amanda comes from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada where she amassed a wealth of economic, technical and industry knowledge through various positions including policy advisor, project lead and Economist.

Amanda holds a master’s degree in Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics from the University of Guelph. She is also a Board member of the Canadian Agricultural Economics Society where she promotes outreach and the importance of agriculture and food research.