'Anything but American' food movement in Canada

Walk into a Canadian grocery store today and you may notice something different. There is a resistance unfolding in the aisles marked by maple leaves and “T’s” identifying Canadian products and those directly impacted by tariffs. Shoppers are no longer just choosing what is fresh or affordable, they’re choosing what feels right to them. In 2025, that increasingly means buying anything but American.

This shift in consumer behaviour is reshaping Canada’s food supply chain. While the United States remains Canada’s largest trading partner, food imports from south of the border are declining. Canadians are turning to other countries and to domestic suppliers. The movement is bringing hope to Canadian food businesses, but it’s also revealing a few limitations of our food system and the complexity of consumer choices.

Domestic food dominates Canada’s processed food supply

Canadians have long shown a preference for homegrown products. This is in line with academic studies that consistently find consumers in developed countries are willing to pay more for food labelled as domestic, compared to an imported equivalent. For many, it’s about supporting local businesses, protecting domestic jobs, and asserting national pride, behaviours broadly referred to as ethnocentrism. Others see domestic labels as indicators of quality or safety, especially when those attributes aren’t easily judged in-store.

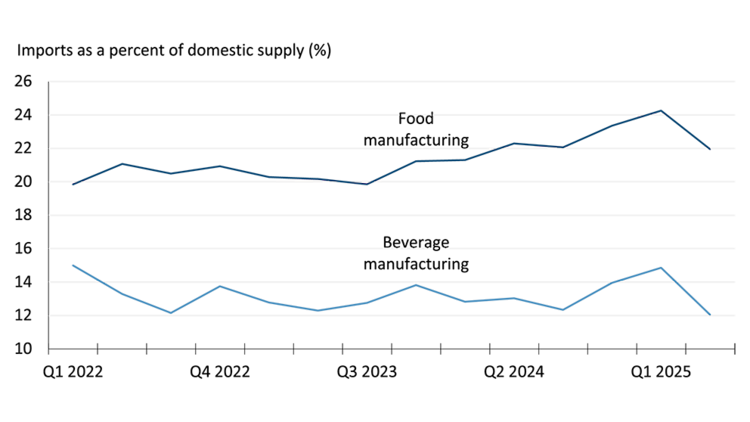

But Canada’s food system also has limitations. Our climate, geography, and production capacity mean we can’t grow and process everything. Since 2014, imports as a share of domestic food and beverage supply have been relatively stable, roughly 20% for processed food and 14% for beverages (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Imports as a percent of Canadians' food supply reach highs in Q1 2025

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

What happened in the second quarter of 2025, just as trade disruptions took hold, is stark. After the processed food import share reached the highest level in recorded data (ie. 2002) in Q1 2025, the very next quarter saw the sharpest quarter-over-quarter drop in import share, falling 2.3 percentage points in food manufacturing and 2.8 in beverage.

Why the sudden decline? A combination of two factors mostly:

Front-loading: Importers may have rushed shipments in Q1 on non-perishable items to avoid looming tariffs.

Consumer shift: Canadians may be increasingly choosing domestic products.

While it will take months of data to quantify the full impact and the root cause, what is undeniable is there is a shift happening in international trade patterns.

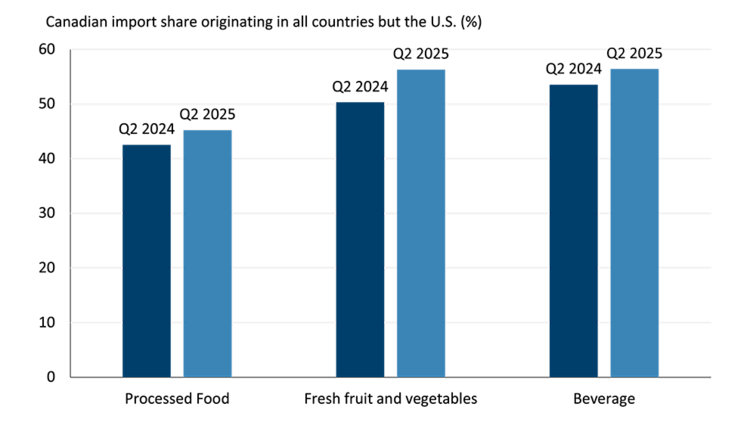

Source of imported food shifting away from the U.S.

Historically, when Canadians couldn’t find what they needed from domestic sources, they primarily turned to the U.S. Proximity made it practical for importers, with shorter shipping routes helping costs and freshness. The U.S. still supplies over half of Canada’s processed food imports and nearly half of fresh produce and beverages. But in 2025, Canadians are looking elsewhere. Imports from the rest of the world are starting to take a larger share of Canadian imports, up from a year earlier across all categories (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rest of the world gaining share of Canadian food imports from the U.S.

Source: Canadian International Merchandise Trade Database

This is also supported by recent research from Food Processing Skills Canada (FPSC) that found 76% of Canadians are motivated to avoid U.S. products, with 43% making significant changes to their grocery habits this year. The top reasons? Anger and frustration with the U.S., a desire to help Canadian processors, and national pride.

This diversification is not only a response to current consumer preferences and tariff costs, but also part of a longer-term strategic move to reduce reliance on a single trade partner. The challenge now is navigating this shift without compromising access or affordability for consumers.

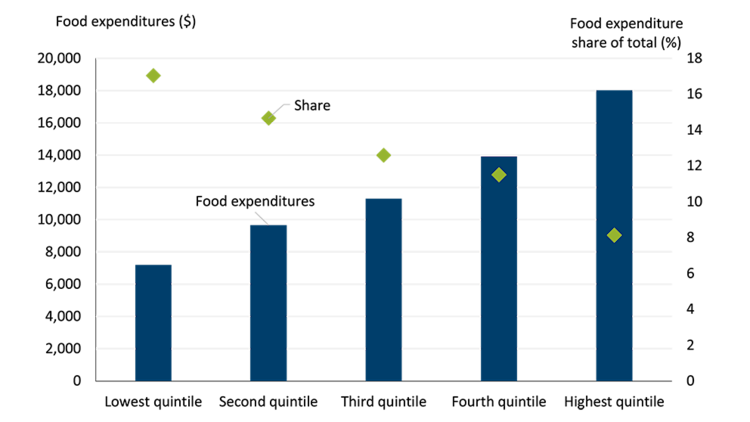

The cost of choosing Canadian

While some Canadians are scanning barcodes and avoiding imported orange juice over politics, others face a tougher reality: they simply can’t afford to be this selective. In 2023, the lowest income households spent upwards of 17% of their total expenditure on food compared to only 8% for those in the highest income bracket (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Share of expenditure spent on food falls as income goes up

Source: Statistics Canada

In 2024, 25% of people lived in food-insecure households, up from 23% in 2023, according to PROOF, driven by inflation, supply constraints, and widening gaps in food accessibility. For these households, the luxury of choice is absent. It’s not about which strawberries to buy, it’s about whether to buy them at all.

Canadians are likely to keep buying Canadian only as long as they can afford to. In fact, the same FPSC survey found that 33% of respondents would maintain their current level of spending on Canadian products until they cannot afford it anymore and 52% said that purchasing more Canadian products has made their grocery bill more expensive.

So, while consumers may express a preference for domestic products, real-world decisions often come down to price, taste, and availability. The gap between stated preferences and actual purchases is shaped by income, access, and necessity. This is important for businesses along the supply chain to recognize when making production decisions.

Supply chain implications

As consumers weigh the value of different attributes, labels have become a focal point. Shoppers are watching closely. In fact, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has seen a surge in complaints about country of origin labelling this year and the term “maplewashing”, where consumers are being misled about a product being Canadian, is making headlines.

This scrutiny reflects a deeper consumer interest in transparency. Today, it’s about country-of-origin. Tomorrow, it might be environmental footprint or ethical sourcing. That’s why investment in traceability matters. Businesses that build strong documentation and supply chain visibility will be better equipped to respond to evolving consumer demands over the long-term.

Clear, honest labelling isn’t just about compliance, it’s about building trust and long-term resilience. Instead of reacting to each trend, companies can communicate the value of their products and strengthen their market position no matter what the consumer is demanding. An added bonus - robust traceability is also crucial for managing recalls, profitability, and export compliance.

Bottom line

While the movement towards domestically produced food is energizing for Canada’s agri-food sector, the reality is that the short-term economic impacts may be modest. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) won’t necessarily rise just because consumers switch from imported to domestic products. Unless domestic production increases, the shift is more about redistribution than growth.

Still, there are benefits. A demand for more domestic processing could mean more jobs and more investment in the agri-food sector which long-term could boost GDP. It is also encouraging that Canadians are taking time to learn about where their food comes from and take a more active role in selecting products in the store. Finally, diversifying trade for the products that cannot be grown here, can help set Canada up to be more resilient in the years to come.

Amanda Norris

Senior Economist

Amanda joined FCC in 2024 as an Economist. She has expertise in the food and beverage industries, but also does research on supply management and consumer trends. Amanda comes from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada where she amassed a wealth of economic, technical and industry knowledge through various positions including policy advisor, project lead and Economist.

Amanda holds a master’s degree in Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics from the University of Guelph. She is also a Board member of the Canadian Agricultural Economics Society where she promotes outreach and the importance of agriculture and food research.