2026 Dairy outlook: The ‘protein craze’ makes waves in the dairy sector

Whether it’s a general shift in consumer preferences, the surge in widespread adoption of GLP-1 drugs in North America, and/or the growing influence of social media personalities, there is little doubt that demand for protein and protein-added products is on the rise. In response, regional marketing boards in both western and eastern Canada are changing how producers will be paid for milk components in 2026. In this blog, we break down the why and the so-what behind the ‘protein craze’ and what it means for Canadian dairy producers.

Consumers are seeking high-protein dairy in pursuit of healthy diets

Less than a decade ago, the dairy sector was in a predicament. Consumers were demanding more products high in butterfat (e.g., cream, butter). On the surface this appeared a positive development; after all, how could more demand for your products be a bad thing? The problem, though, is that at a given point in time the components of milk are structurally fixed between butterfat, protein, and other solids (OS). So, to meet that additional demand for butterfat in the short-term, more milk needed to be produced; this, however, created a surplus of the other components – namely protein – that processors and consumers didn’t want at the time. Simply put, the sector was faced with a structural surplus of protein.

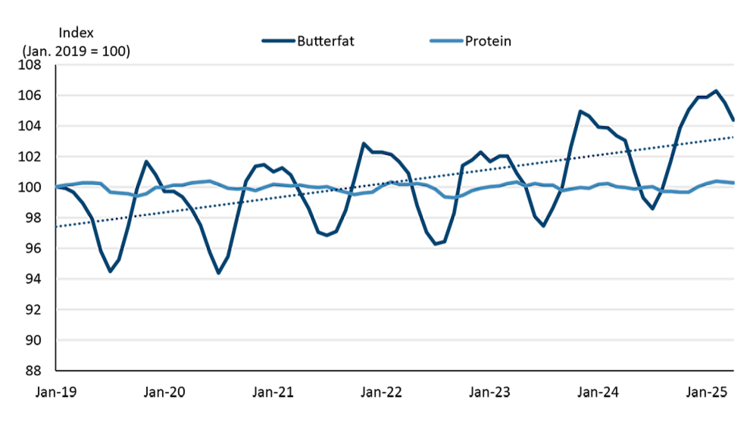

In response, milk boards restructured producer pay on these individual components – placing a greater dollar value on butterfat – with the aim to incentivise farmers to produce more of it. Through changes in breeding strategies and feed rations, the industry responded. Today, the Canadian dairy herd is producing more butterfat per litre of milk than ever before. For example, in Ontario over the last six years butterfat composition has increased 0.9% per year on average. Conversely, the percentage of protein has remained flat (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The amount of butterfat in Ontario milk has been on the rise

Sources: AAFC, FCC Economics

That situation is now reversing, and the sector is staring down a protein deficit rather than a protein surplus. Part of the reason is demand for dairy products with higher protein content, such as yogurt and cheese, saw significant growth in 2025 (Table 1). This occurred despite the slowdown in population growth which had been a key driver of sales between 2022 to 2024.

Table 1: Consumption of most dairy products has accelerated in 2025

2024 growth | 2025 growth | |

|---|---|---|

Yogurt | 0.8% | 8.0% |

Ice Cream | 2.1% | 4.3% |

Butter | 2.7% | 4.2% |

Cheese | 1.7% | 3.2% |

Cream | 1.6% | 0.6% |

Milk | 1.1% | -0.1% |

Sources: Canadian Dairy Commission, FCC Economics

So, what’s behind the rise in consumption if population growth has slowed dramatically? One of the main reasons why is consumers are seeking diets that are high in protein. In the most recent International Food Information Council's Food and Health Survey respondents voted “good source of protein” as the number one criteria used to define a healthy food, taking over the number one spot from “fresh” which had held the top spot for three years in a row. Accessible foods full of nutrients – like dairy – are appealing to health-conscious and time-strapped consumers. However, non-dairy food manufacturers are also riding the wave of the protein craze, with added protein now appearing in a variety of products that are naturally not high in protein including waffles, Pop Tarts, and even Doritos. This is providing another opportunity for dairy protein to be used as an ingredient.

Producer pricing is changing to incentivise more protein production

In response to these changing consumer preferences, milk boards are adjusting how producers are paid for their milk components. Beginning in 2026, in both the P5 (eastern Canada) and the WMP (western Canada), there will be a greater dollar amount placed on protein components.

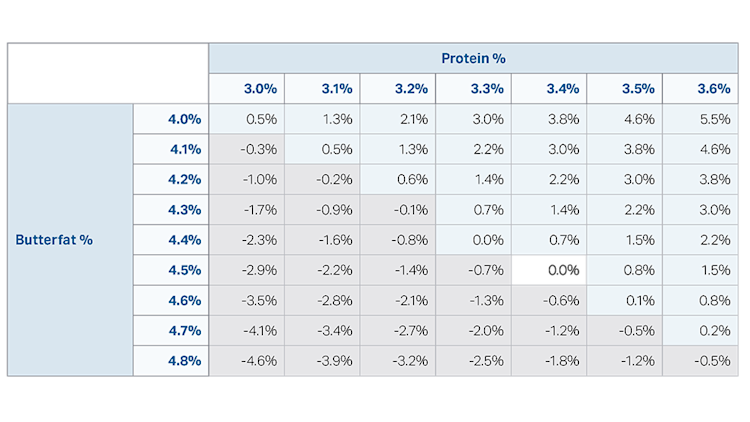

What does this mean to producers’ bottom lines? Let’s say a farm in the WMP has milk that is currently testing at 4.5% butterfat and 3.4% protein. If the farm’s average milk composition stays the same, under the new pricing structure they will see a negligible difference in their gross revenue (0.0%, highlighted in bold in Table 2 below). But say they increase their butterfat percentage to 4.7% while keeping their protein percentage at 3.4%. In this scenario, their revenue will fall -1.2% compared to what they would have received under the old pricing system. Conversely, if they lower their butterfat to 4.3% while keeping their protein at 3.4%, they will increase their gross revenue by 1.4%.

Table 2: Impacts of WMP’s new pricing structure under different milk composition scenarios

All percentage changes are relative to the current pricing structure with average milk composition of 4.5% butterfat and 3.4% protein.

Source: BC Milk Marketing Board, FCC Economics

While the pricing mechanisms and dollar amounts look slightly different in the P5, the general patterns and directional price changes are still the same.

But what about butterfat?

This does not mean demand for products high in butterfat is down. But, in the short-term, there is a risk that we could see an abundance of butterfat as the industry readjusts and realigns to these changes in consumer preferences.

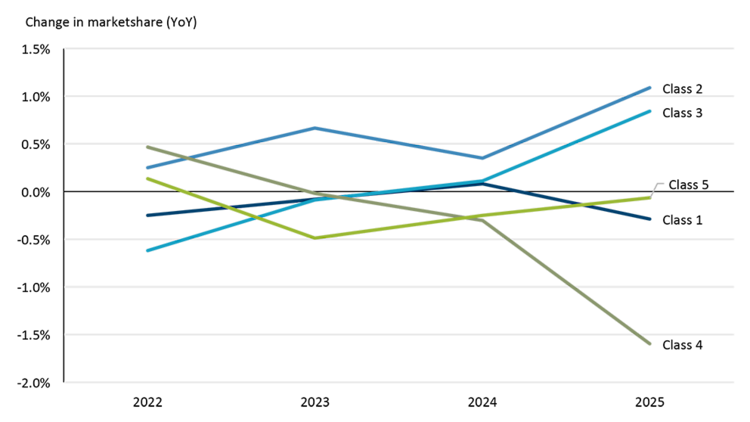

According to the Canadian Dairy Commission (CDC), stocks of butter have been higher in each month of 2025 compared to the same month in 2024. This, despite Table 1 showing butter consumption is up 4.2% year-to-date. What we noticed last year was that processors began directing less milk into making more butter, presumably as the sector attempted to burn through these high butter stocks. Last year, only 18.4% of milk produced in Canada went towards Class 4 (butter) processing, down from 20.0% the year prior, a decline in market share of -1.6% (Figure 2). The main takeaway here is that if the percentage of butterfat in milk produced on-farm cannot be lowered while protein production is ramped up, the sector may be faced with an even higher butter stock than exists today.

Figure 2: Less milk (by volume) has gone into butter (Class 4) this year

January through to October each year.

Source: AAFC, FCC Economics

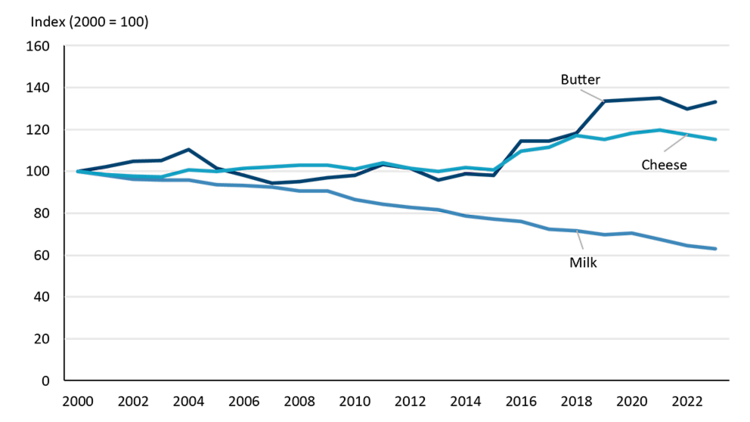

Another question that’s arisen is, does this protein craze have staying power? After all, it will take years and successive generations of breeding to shift the herd towards higher protein / lower butterfat producing animals. The previously mentioned surge in demand for butterfat last decade has had staying power. On a per capita basis, consumption of butter (and to a lesser extent, cheese) has remained stable since 2019 (Figure 3). While there’s no guarantee the protein trend will have similar staying power, the outlook is positive. Third-party research providers are forecasting that in the medium-term growth in this market will be steady. Euromonitor, for example, is estimating protein packaged food product sales will be $1.63 billion in 2027, up from $1.39 billion in 2024.

Figure 3: Per capita consumption of butter has maintained its ascent that began in 2015

Source: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

Bottom line

There are reasons to be optimistic about the dairy industry in 2026. This summer’s CUSMA review will be a watch-item for industry stakeholders but until that process is complete and the details known, producers would be wise to continue focusing on what they can control on the farm. As discussed above, the aim of the new pricing structures is to incentivise lower butterfat volumes while also increasing the volume of protein. It will be a multi-year endeavour, but producers should begin thinking now about potential changes to herd management, breeding strategies, and/or feed rations to make the most of the new pricing structure moving forward.

Graeme Crosbie

Senior Economist

Graeme Crosbie is a Senior Economist at FCC. He focuses on macroeconomic analysis and insights, as well as monitoring and analyzing trends within the dairy and poultry sectors. With his expertise and experience in model development, he generates forecasts of the wider agriculture operating environment, helping FCC customers and staff monitor risks and identify opportunities.

Graeme has been at FCC since 2013, spending time in marketing and risk management before joining the economics team in 2021. He holds a master of science in financial economics from Cardiff University and is a CFA charter holder.